There are many versions of Arrirang. I read somewhere that each region has its own. This one the tune is not familiar, but it feels more traditional. The youtube poster accompanied it with some amazing photos of Korea a century ago.

impressions on making important statements through art

I only just now found time to sweep my floor of art installation debris from the sweatshop that my apartment became. Despite my best efforts, a fine grit of white powder still clings to the floor and every surface, the by-product of needle punching fabric and scissor blades grinding. It will take several passes of hand cleaning in typical ajumma fashion to restore this place to livable again.

I have also managed to have two showers in my own home this week! And slept over four hours! I even managed to wash a load of laundry and hang it to dry on the veranda. Such a treat after a week and a half of taking the train from CheongPyeong immediately after school to Seoul, working until you can’t see straight, and then getting up at quarter to 5 to catch the first train back to the day job teaching by 8 am. A four-hour commute every day, except for the two times I slept over night in the National Assembly, which will always bring a smile to my face as Jane slept with the kangaroo suit on to stay warm, while we covered Daehan with a blanket and I wrapped myself up in the reserve white fabric panels of the art installation. Thank you nice security man for allowing us to do that!

I’m not telling you this to elicit sympathy or admiration — Jane looked at me one time and said, “you really are in your element, aren’t you?” And it’s true. Nothing’s better in the whole world than when you’re engrossed by purposeful work. It’s existential. I’m telling you because this wasn’t about anything but a burning drive to complete this opportunity. This thing had to come out, no matter what. Like a compulsion/obsession. This has been my privilege, and there will be a void after the smoke clears.

Jane has mentioned several times how this process has changed her. For me, it was a reminder that imperfection is beautiful. Back in Architecture school, we had to draw 5 minute sketches and I hated each and every one of them. But the complete ouvre of those sketches, all assembled together, made such an impact. And the imperfections disappeared. Or stood out as wonderfully human. It enhanced instead of detracted. Soooo many things were not as I had wanted, and I just had to let it go. (Hundertwasser could assemble an entire army of devotees among adoptees rallying against the straight line.) Jane jokingly called me a Diva once, and I had to work even harder to just let things go. In the end, the installation looked surprisingly almost exactly as I had envisioned it. Multiply a factor of deviations times ten, but it still managed to hold its integrity.

I did spend quite a bit of time adjusting and re-working things. Typically not from an aesthetic point of view, but from a basic – this doesn’t work in the physical world kind of view. Ha ha ha! The one thing that just blew me away was how un-handy everyone was! This old broad just couldn’t comprehend how unfamiliar everyone was with basic hardware store items or the most rudimentary fix-it techniques. These blue-collar working-man things are my whole life, so I can’t fathom a world devoid of them.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, despite my best efforts, I found myself totally failing at explaining this project to people — largely because people didn’t want to know or get into technicalities. “Just tell me what to do, ” :( Jane and others said several times. Me, I wanted to just work in mindless zen too, but everyone kept making me be boss-man, fire-fighter, traffic director.

Of course we were at near disaster several times: the connectors we’d ordered from the U.S. were in inches but our Korean pipes, though they told us they were in inches, were actually in metric units. There was so much slop between the pipe and connector that nothing we did could make the connectors viable, and we were left with a tunnel consisting only of hinges that could barely stand. And so we had to do a complete re-design on a tenuous shape and then all the work we’d done on the casings became irrelevant. Although nobody was handy we had plenty of arm-chair engineers and two soft trained-as-architects who are more accustomed to hiring engineers than thinking about structures. Everyone/all of us were only half right half of the time, and so we just kept experimenting until the damn thing stood up! In addition, the adhesive on the velcro strips didn’t like the polyester and it started separating. Jane’s brilliant response was to tack the sections together with the tag hanging gun. I took it one step further and found that by passing the needle through several times we could “stitch” the piece together adequately.

My happiest moments were the night I stayed alone over-night. I just arranged the tags and photos mindlessly, adjusting and thinking and caressing the project. I finally got a few moments of zen. Ha ha! You can tell in the photos that everything my height and lower is more ordered…I must have a mild case of OCD. My mind tries to embrace the variations, but every fiber of my being wants to make order out of chaos…

The zen of repetition had a wonderfully strange effect on everyone else: it produced a magnanimity of spirit and a sense of higher purpose that felt something like synchronicity. I guess the word for that is fellowship? No. Comradeship. I missed a lot of that, unfortunately. It’s lonely being in charge, running around.

I only got misty eyed twice. One time was when I was describing to the BBC reporter how I’d refused to read the Holt book, “Seed from the East,” and how the book would just magically appear in various places along my daily path. My heart just broke thinking about how very much my mother wanted me to be thrilled with being adopted. We weren’t the only victims, us adoptees. The other time was when Amanda was showing other adoptees one of the referral photos hanging on the tunnel wall. “This is my friend,” was all she said. But for some reason it was the most poignant thing in the world to me, her friend there among the tens of thousands of other adoptees/tags. That we can have relationships so meaningful. There is hope among the ashes.

The goal was to bring the lawmakers to their knees, but because of fire safety code we could not block the exit path because our tunnel was too narrow – and so we were forced to not force the legislators to walk through, had to move the installation to the side, and many elected to pass by. But towards the end and at the final ceremony, it became clear that the project was really for us adoptees, as validation of ourselves as a diaspora, of our humanity, and our loss. We can look to its message – and send its message – for some time now.

One Korean national told me after seeing the installation that she was embarrassed and ashamed by her country. That she had NO IDEA 3 children were still leaving every day. That it is wrong Korea can’t take care of its own people. That all Korea needs to know about this. I felt good after this. I felt like a good day’s work had been done.

It was a shame we couldn’t leave it up for another week. The Yongsan massacre artists were there, waiting to replace our installation with theirs. At first they wanted to use our structure so we cut the fabric panel casings off instead of sliding them off, which would have required dis-assembly. A poor decision on my part. As we cut through the casings, one of the unwed mothers burst into tears. I think our expression and huge efforts to support this bill supporting them blew her mind. I think seeing what she almost lost also blew her mind. Seeing her so moved blew this adoptee’s mind.

I want to take a moment out and thank the Korean who told us we couldn’t do this. It’s just not wise to tell me there’s something I can’t do, because I spent too much of my life being told: you can’t make it in architecture school, you can’t make it alone, you can’t have your adoption records, you can’t…I know that’s b.s. I know everything is possible. Like the t-shirt Jane wears that says, “Attack to the rotton world!” I’ve survived this adoption experience and no further constraints are acceptable.

Thank you to all the adoptees, friends of adoptees, and Korean nationals who came out to help, putting themselves on display as part of the art, and toiling for the cause despite thinking I was sadistic, especially those adoptees who showed repeated dedication and went out of their way to make the project a top priority, those adoptees visiting only for a week or two who sacrificed so much of their trip to help with the installation. Thank you to Rev. Kim and the dancers. Thank you to Alice and her entire family. Thank you to everyone who came out to CheongPyeong prior to the installation. Thank you, installation, for letting me get over my fear of other adoptees a little to meet some new friends.

And last but not least I want to thank Jane, who also knows everything is possible and who also sees art in strange places. At no time ever in my life has anybody ever just believed in me without reservation and with full support. I feel loved. She is my mother and sister (and yours too). Her compassion is the driving force behind all the work that we do. TRACK gets things done, and it’s fueled by her love. (and Paella from Provence – thanks Greg!)

The inevitable mistakes of mass production

I’d just like you to know that my Korean friend Miwha has posted a great photo essay of the art installation on her DAUM blog.

Please share this with your Korean-speaking friends and Korean national friends. Thanks!

above photos by Lee, Miwha

Explaining the installation to the lawmakers while Rev. Kim translates.

A Collection of One

The art installation we’ve been working on the past month is to illustrate the relationship between the number 1 and 200,000. We lose sense of the impact of our actions when we allow ourselves to look at only the number right in front of us. The reality is that 200,000 is almost unfathomable. This is an attempt at showing what one looks like, 200,000 times. One adoptee at a time, processed in the perpetual motion machine that is international adoption.

Something resembling the speech I gave (was told to, “make short your speech” midway through, so much got cut) at the National Assembly reception for the art installation:

Over three years ago I left a full time position for a part time job, so I could have the time to pursue creating art. However, I failed. I was confused: I couldn’t express myself and had nothing to say. But because of a personal crisis, instead of creating art, I ended up using all that time thinking about how I ended up where I was in my life. For the first time ever, I began to think about international adoption and its impact on myself and everyone like me

Now that I’m in Korea, I find myself having too much to say. This piece is part of that.

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about numbers. Well, actually I guess I’ve been thinking about numbers for all my life. Mostly about one number, by itself, which I think is very common among adoptees, as they must by default bear their losses on their own when they are sent to foreign countries – where no one in their families can understand what it is to look different, or to be disconnected from those that look like them, or have to explain their existence, or try to reconcile why they were given up. One is the number we adoptees know too well.

When I read statistics about the number of social orphans (children with living parents but called orphans) created each year I get so sad. When I am told to be happy because the numbers are decreasing, it doesn’t cheer me up because every social orphan created means one more child who must learn the meaning of one on a profound level. Being exiled from your mother, your mother country, and your mother tongue is a loneliness I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

These days, on average, approximately 3 children a day are sent out of Korea for adoption. During the peak year of international adoptions, 1985, the average was more like 10. They are both small numbers, yet they add up. In Korea’s case, they add up to almost 200,000. To me, 3 children a day is one lifetime + another lifetime + another lifetime. 3 is a huge number to me.

Here in Korea, I watch and listen and try to love this place. I try to understand why my country threw me away, and I think I can and I think I forgive. But I can’t understand why there are still 3 more children leaving every day. In a rich country without war or famine, there seems to be no valid reasons for creating orphans out of children with living parents. And as I learn about the excuses why 3 children continue to be thrown away every day, I sometimes think I am glad I was sent to America. Because in America, I was able to be a single mother and go to college and have a career, because my government helps take care of its citizens, and I know that I would have struggled twice as hard and been cruelly judged here in Korea. Thank goodness my children, the love of my life; my reason for being, weren’t born in Korea, or someone might have forced me to send them away for adoption.

Preserving family honor by eliminating an innocent person is not an honorable act. Hiding dark secrets is not an honorable act. Creating an industry out of disappearing children is not an honorable act. Preserving one family by destroying another is not an honorable act. No. This is the opposite of honor or family values. This is hypocrisy.

Penalizing women for indiscretions or unfortunate circumstances not only hurts the women and their children – but it also hurts Korea – in both potential citizen numbers and emotional trauma to society at large. These women are no disgrace to Korea: KOREA’S NEGLECT OF THEM is the real disgrace, and the resulting expulsion of their children abroad makes Korea look like a third world charity case. These women who choose to face their mistakes and bear their responsibilities indicate a true strength of character and maturity that is missing from the claims of many Koreans, typically their harshest critics.. (We have a word for people who try to hide in shame: cowards. Cowards are threatened by those with integrity). Any woman who chooses to prevail in this harsh climate so she may raise and nurture the flesh and blood she brought into the world is brave and deserves all our support.

So instead of penalizing these women, we need to assist them. It is an investment in a stronger Korea, as every child lost to lack of social services equals a loss of human potential. (Well, not to the other countries who receive them, but certainly a loss of human potential for Korea) And the kind of potential that comes from difficult beginnings forges the strongest character, which is endangered in these soft times. That’s a huge loss for Korea if this country intends to persevere in the future.

As an ethnic Korean I want nothing more than to be proud of being Korean, but I can’t – because in the rest of the world Korea is still known as the best place to get unwanted babies, as a mean race that ostracizes and oppresses women, and as barbarians who eat their own pets. I believe Koreans want to be proud of Korea too, and so we should find real solutions which strengthen society instead of perpetuating practices which cause pain and literally diminish society.

Adoption has been the easiest solution for the government for the past 50+ years, but it does not solve social problems and, I would argue, cutting off children from their mothers is maiming Korean people and Korean society, because it forces all Koreans to live with the stain of being the kind of people who throw away their own children. Adoption has been the solution of choice because it’s easier to sign away one number with one signature than it is to acknowledge that each and every number is a human being that deserves a chance to live their lives as God and nature intended.

My prayer is that Korea comes to value all life and all families, both perfect and imperfect, so that no more one-way travel certificates out of Korea are forced upon little people. Let this congressional session show the world that Koreans are not barbarians but enlightened people, creating a civilized society that takes care of its own citizens

Girl #4708

June 15th, 2010

With only one month’s ’round the clock organization, adoptees visiting or living in Korea have united as a community to make this idea a reality, getting assistance from Korean nationals and unwed moms.

Over the course of two weeks, 90,000 price tags were stamped with an individual number representing one adoptee.

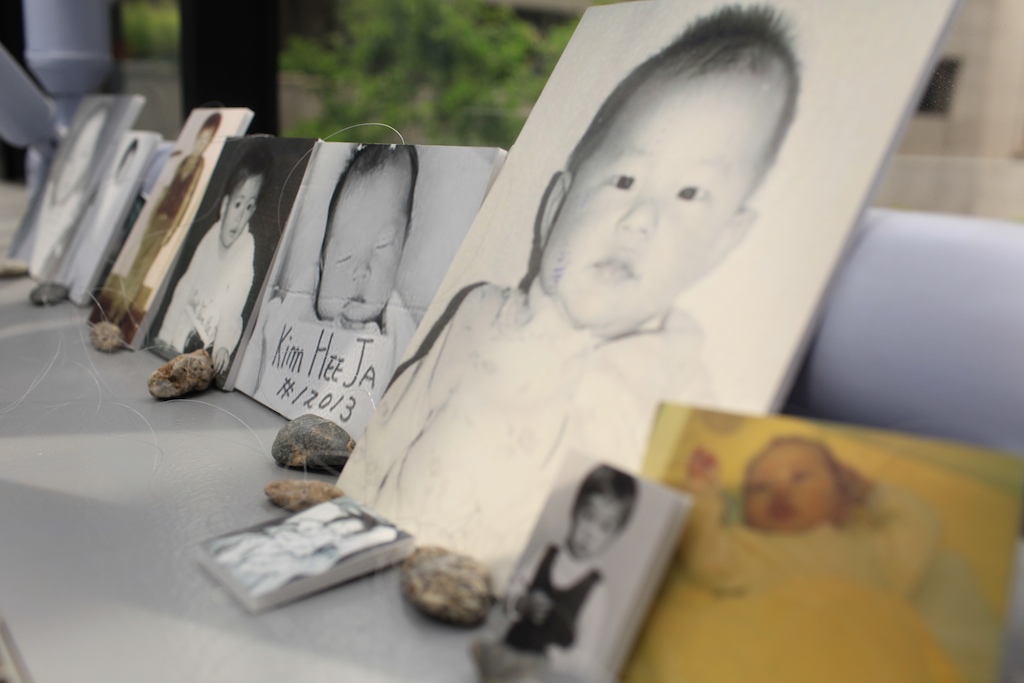

Over 75 referral photos were sent in from all over the world.

Over the course of the six day installation, approximately 60,000 tags were hung.

We fell far short of the 200,000 but had known all along that would be impossible.

photo by Jes Eriksen

I’m exhausted but it feels wonderful to do purposeful work.

everything’s white

Almost halfway to the first rough cut. The rough cut is necessary just so it’s a manageable (cough) piece. Then, I have to determine where the two casing will be stitched from the middle and mark it with a pen, and then from there measure where the exact hem will be. Some other radical feminist adoptees are going to come over and help me Sunday. Thank God – it’s six days to show time! …I’m going to have them help me mark dots on the fabric so people can locate where to hang their tags. That will be done with chalk dust, hopefully. Making a jig with a lot of holes in it and will beat it with a sock full of chalk dust… And since I only have one sewing machine, maybe we’ll take turns sewing the casings on. The hem will be done with double-sided tape. Sounds easy, but have you ever tried to keep 6′-0″ of tape straight working with really lightweight fabric that’s mostly a spun polyester?

Each roll is 50 yards. I’ve gotten through 4 so far. Only one of me, and 600 yards of fabric. This would not be so daunting if there was one other person here, so they could join the two pieces while I cut or vice-versa. I really wish I had a video camera person here right now. The fabric billowing as I pull it off the roll is really beautiful. Arm over arm over arm as I measure each piece, my knees crunching on the floor as I bend down to cut each one. the workout of this act is just one more piece of the picture that, other than me stopping to take these still shots which are totally inadequate, makes up this work.

Jane and I are beginning to hear supportive words from adoptees all over the world and getting some participation here in Seoul. It’s like a mad race now to see just how much we can do/how much we can do in a short time with limited manpower, to get our message across.

Anyway, if I was a praying person, I’d pray for a seamstress to come live with me for the next week. Anyone?

worth every second

It’s 3:39 am and I’m taking a short break. I haven’t eaten dinner yet, and I have to leave in 6 hours to head to Seoul. I’m going to the salon, because every other time I’ve been in front of a video camera I’ve looked like hell. Well, I’ll probably look like hell this time too, because I’ll have worked two weeks straight like I am now on top of my day job. But I’m excited and optimistic and energized despite being totally run-down.

Just now I unrolled 150 yards of fabric (well, actually I have about 20 more yards to do) and cut it into 7 meter lengths. Let me tell you: that’s a real workout! It’s like doing 60 downward dogs, fast, all in a row…That 150 yards was from way back when – when we were going to get tiny tags and pack them in real tight. Now, we need 300 more yards, which will be delivered to my school so I can do more of this. Right now I’m sewing two 1 yard wide panels together. After that, I have to put tent pole casing on three sides and velcro on another.

7 meters is really long! Once sewn, it makes a tunnel section about about 9 feet high by 6 feet wide by 6 feet deep. Now multiply that by 28 times. The tags will be really crowded. If I’d designed it to have a little breathing room on either side, it would have ended up about 10 feet longer than a football field. To give you an indication of the enormity of this project, each tag is 4 cm wide by 8 cm. long. That’s about 1.5 inches wide by 3 inches long. 200,000 of them overlapped by half, in a tunnel 9ft. high by 6 ft. wide, shoulder to shoulder, is about 12 feet shy of a football field. And that’s just little tags…

It isn’t making me cry YET, probably because I am taking care of the canvas. Maybe tomorrow when I go to help stamp a number on each tag I will. It’s definitely affecting everyone who’s working on the project. I worry about Jane, surrounded by all those little tags. You can see what she’s up against at the TRACK website. A Korean saw a small portion of the tags, which is a huge quantity, and said, “I’m so ashamed to be Korean right now.”

Let’s hope the lawmakers feel the same way.

You know, people have been confused by the project. Nobody really understood that the art was not in the product, but in the doing. It was never meant to be easy. It was meant to reflect the reality of processing adoption.

I was asked to give an artist’s statement, and so I wrote the following. It’s currently being edited for Korean culture, (because I thought Han meant Korean people) but says what I wanted to say.

A collection of one

the art instigator’s personal statement

The Korean in me wanted to tell the Korean in you something, as the one people we should have been, and the one people Korea can be in the future, and so I shall talk about our adoption experience in terms of we…because the adoption experience is not just the adoptee’s problem, but uri problem.

Most Koreans have never met an adoptee in real life, though almost every Korean knows of a family member that was affected by the disappearance of a child, a child who was born a Korean but is now only a guilty whisper at family confessionals: a distant memory for many and a fresh wound for many more. In each Korean family clan there are child-shaped holes, and in the space of their absence is a void that can’t be filled and can only be covered up.

These children are the memory we want to forget but never can. They are on our minds like bad dreams and spill out on our paper, canvas, and screens. And so we return — again and again and again — to re-live the pain of our loss, in the hope we can somehow find resolution to absolve us of this act committed against nature and humanity. We want it so badly, this resolution, and in the deepest way. But we are trapped in a never-ending inconsolable loop, because we not only exiled our children from us, but we also exiled ourselves from our children. We not only harmed them, but we also harmed ourselves: on so many levels. How many knots must this nation untie due to adoption?

This internal haunting of conscience is our eternal fate as a people, as a nation, and as individuals, unless we stop throwing away our children and face the ugliness of our own actions: so that we may right our wrongs, heal our wounds, and make a better society for our now endangered Han. And in order to do this, we must finally open our eyes, look at the consequences of our actions, take ownership of them, and correct our ways.

The Korean adoptees who have returned recognize that adoptees are not real to Koreans. They don’t look like the foreigners they’ve been forced to become. There is no way to distinguish them from other Koreans, because they are Korean. At most, they are an anomaly, a momentary disruption in the fragile pride we have over the sacrifices we’ve made for success, and easily dismissed in the habit of purposeful forgetting. A futile forgetting.

In a collectivist society, one has no meaning. And adoptees are always portrayed in terms of one. And when they come to visit, they come one at a time. And when they were thrown away, it was one at a time. By profiling the adoptee as one, we don’t allow the lone adoptee, the anomalous adoptee, to penetrate our task of protective forgetting. Yet they are not one. Each and every child sent away is a person: a person who’s absence has left a deep scar on the soul of Korea.

All together, approximately 200,000 Korean children were sent away from Korea without a choice.

Of those, only an estimated 500 have returned as adults to live in the country that threw them away.

As one of the 500 who has returned, I wanted to show you what 1 Korean adoptee looks like, 200,000 times.

And as one of the 500 who has returned, I’d like to see Korea redefine family so that it values all Korean blood,

so Korea loses no more Han and I never have to hang another tag.

girl #4708